The Town Council Struggles to Address Residents’ Concerns While Complying with the Law

Those who attended or viewed the live stream of the September 4th Town Council Meeting witnessed an extraordinary example of how dysfunctional those proceedings have become since ROT came on the scene two years ago. The meeting’s agenda included the adoption of the proposed amendments to Zoning Ordinance Chapter 17, Wireless Telecommunications Towers and Antennas. At the conclusion of the Public Hearing the amended ordinance was approved and adopted by the Town Council by the now all too familiar 4-3 split. But in the process, there was a lot of spewing, threatening, complaining and accusing. The acrimony was particularly remarkable because Chapter 17 does not even address the regulation of the issue that has caused the most consternation: the installation of antennas necessary to support 5G technology in Fountain Hills.

BACKGROUND

5G and Fountain Hills

It is indisputable that as a country and as a community we increasingly rely on portable wireless devices to manage our lives and our businesses. To meet the demand for increased speed and processing capabilities the telecommunications industry must build a next generation wireless communications network.

The Fifth Generation (5G) standards for mobile wireless networks require a greater bandwidth to support more complex devices and faster downloads. 5G wireless technology requires a denser, shorter network of antennas to function properly.

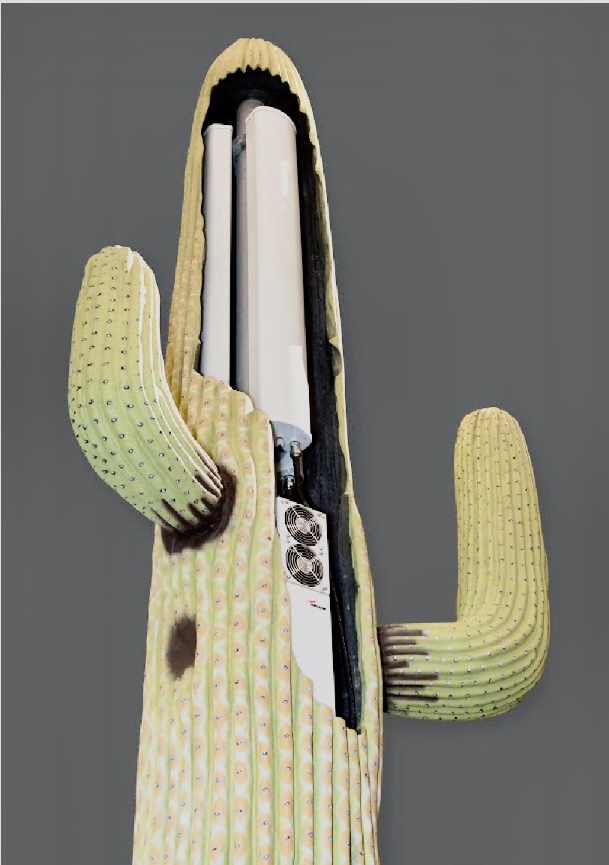

5G is distinguished from older technologies, because it relies on millimeter waves allowing for a tremendous increase in data speed and volume. However, because millimeter waves travel shorter distances, the technology is dependent on the addition of Small Wireless Facilities (SWFs) to the communication network. The spacing between SWFs can, depending on the demand, range from a block to a mile as compared to large cell towers which can be miles apart. To function properly an SWF cannot be obstructed – it must be publicly visible.

An SWF typically consists of radios, an equipment box and one or more antennas. The facilities are intended to supplement, not replace, existing networks by providing increased capacity for data transmission.

Subject to regulatory approval, SWFs can be placed on public property, in rights of way (ROWs) or, with the owner’s permission, on private property.

To date, there are no SWFs located on Fountain Hills public property or in its ROW. Currently no applications have been submitted.

To support the rapid expansion of 5G technology the FCC has promote the use public rights of way, as opposed to private property, to place SWFs. As noted above, an SWF cannot be placed on private property without the permission of a property owner. This permission is generally granted through a lease agreement. Given the number of SWFs necessary to support 5G, placement on private property is not viewed as a viable alternative to the use of ROWs.

The federal government by statute, and through regulations, enacted by the FCC, prohibits local governments from banning SWF’s and limits their ability to regulate their placement. Local governments can regulate for aesthetics, design and control of the right of way.

The alarm sounds

Beginning in 2022, a small but vocal group of residents began sounding the alarm claiming that the introduction of 5G technology to our community threatened the health and well-being of the residents. Their concerns, expectations and demands have set up conflicts that have become increasingly contentious.

Residents’ concerns result in a moratorium

In 2023 the opponents of 5G convinced a majority of the Town Council to vote in favor of a Resolution calling for a “moratorium” on the creation of a 5G infrastructure in Fountain Hills. The Resolution instructed “all utilities operating in the Town of Fountain Hills to cease and desist the build out of so-called ‘5G’ wireless infrastructure until January 31, 2024.”

The stated purpose of the moratorium was to allow the Town Council time to review and update its existing regulations to ensure that the “equipment and method of service delivery of communications not protected in the 19(Telecommunications Act)(services other than Cellular Type II communication), are delivered vis methods that do not devalue property values and are deemed safe to the environment and human health.”

From the outset, the Town Attorney, Aaron Arnson, advised the Town Council that the moratorium would not have any meaningful legal effect because “federal law largely preempts state and local regulatorily authority over wireless facilities and small wireless facilities, except for reasonable aesthetic requirements.”

Arnson also advised the Town Council that the FCC had approved a “shot clock” requirement that allowed local governments a limited time frame (60 to 90 days) to approve an application. The Council was advised that the moratorium would not pause the running of the shot clock. An application made during the moratorium could not be challenged and would be automatically approved if the applicable “shot clock period” expired while the moratorium was in effect.

The limitations on regulation imposed by the Doctrine of Preemption

Based on the accusatory and often false statements made during the Public Hearing and posted on social media it is apparent that many residents do not understand the preclusive effect of the “Doctrine of Preemption” when it comes to the regulation of the telecommunications industry.

Preemption is a doctrine of constitutional law that applies where there is a conflict between the law of a higher level of government and the law of a lower level of government. Where there is a conflict, the law of the higher level of government takes precedence. In the United States, under the Supremacy Clause to the Constitution, federal law is the “supreme law of the land”.

For decades cities and towns have relied on their zoning codes to regulate the placement of wireless communications equipment. Provisions, incorporated into zoning codes were used to determine where telecommunications equipment, including cell towers could be installed or built.

The federal Telecommunications Act of 1996 limits the ability of state and local governments to regulate the placement or proliferation of telecommunications equipment that is used to provide personal wireless services. Any provision of state or local law or regulation that would prohibit or have the effect of prohibiting the provision of personal wireless services is not enforceable.

The challenge for local government has been how to regulate the placement of these facilities without running afoul of federal law that prohibits any law or regulation that would “prohibit or have the effect of prohibiting the provision of personal wireless service.” The FCC is charged with enforcing this law and has taken an expansive approach to its interpretation and an aggressive approach to its enforcement.

During the recent Public Hearing, one of the speakers, Crystal Cavanaugh, accused the Town Attorney of “tossing about the term preemption to shut down discussion saying we as a local entity can’t override big government regulations or put protections in place for residents is not acceptable or necessarily accurate.” Although it may be “unacceptable” to Ms. Cavanaugh and others, when it comes to in this provision of the Telecommunications Act, the courts have consistently found that “big government regulations” trump local government regulations.

The validity of the concern

The opposition to 5G in Fountain Hills, as in other communities, is based, in large part on a belief that exposure to electromagnetic fields is harmful to the health of humans and animals.

According to the World Health Organization (“WHO”) during the past 30 years more than 25,000 articles have been published on the biological effects of exposure to non-ionizing radiation. Based on what it described as an “in depth review of the scientific literature” WHO concluded that “current evidence does not confirm the existence of any health consequences from exposure to low level electromagnetic fields.” https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/radiation-electromagnetic-fields.

WHO’s determination provides little comfort to those who sincerely believe that their health has been or may be damaged by EMF exposure, and they take no comfort in statements like this, found at the end of WHO’s “current evidence” statement: “However, some gaps of knowledge exist and need further research.”

Without regard to the sincerity or validity of residents’ beliefs the federal government has determined that local jurisdictions cannot regulate transmission facilities or equipment based on concerns over the harmful effects of exposure to non-ionizing radiation so long as the emissions fall within the federal standards.

Local governments that have challenged the FCC have not fared well in the resulting Enforcement Actions.

The Amendment of Chapter 17

Chapter 17 of the Zoning Code addresses towers and antennas other than SWF’s located in the public ROW. The ordinance addresses permitted uses, special use permits, setbacks and separation. Set back and separation requirements have been established to alleviate the risk of damage to adjacent properties. The ordinance also addresses aesthetics, landscaping and visibility recommendations. Finally, the ordinance sets out the necessary administrative approval process.

The Public Hearing

As noted above, the approval process was marred by contentiousness that began when Councilmember Skillicorn raised a “point of order” and called for the matter to be “tabled” because, prior to the hearing, Vice Mayor Kalivianakis circulated a document containing her suggested changes to the language of the proposed amendments to the ordinance.

Skillicorn’s point of order was properly overruled by Mayor Dickey, on the grounds that the Vice Mayor, like any member of the Town Council, had the right to suggest changes to the language of proposed amendments to an ordinance during the approval process. The fact that the Vice Mayor provided other members of the Town Council with written copies of her suggested revisions did not violate any procedural rule or provision of the Open Meetings law.

Public Comment

The period set aside for public comment was particularly acrimonious and, at times, ugly. Much of the acrimony appeared to result from fundamental misunderstandings of the limitations imposed on the Town Council’s ability to regulate by the Doctrine of Preemption. Other concerns were more specific and often unwarranted.

The concern that the ordinance did not require the applicant to provide insurance coverage.

Many of the commenters appeared to be operating under the mistaken belief that the ordinance left them “uninsured” in the event of an accident or injury involving a cell tower.

For example, during her public comments, Liz Gildersleeve claimed that if a cell tower “toppled” during a monsoon and caused damage to her home she would be “uninsured” because the zoning ordinance did not require applicants to purchase insurance that would cover her. Lori Troller, similarly concerned about falling towers, gave the following example: “I got a tower in my ROW that falls on my driveway, my child gets hit I have to sue, I have got to get medical coverage for my child got burned or whatever.” Troller went on to say that she could not “go to the towers” because the ordinance did not “hold them responsible”. Troller went on to say” So I come to you to you, [the] Town can’t get that insurance it doesn’t exist the insurance companies don’t offer that insurance because it’s a huge loser”. Troller went on say: So it comes down to everybody who says “yes” you’re going to be responsible for everybody’s house’ .

It seems highly unlikely, if not impossible, given the ordinance’s separation requirements, for a cell tower to fall on private property. The separation requirement for a single-family residence or duplex is 200 feet or 300% of the tower’s height, whichever is greater. There is no separation requirement that would apply to residential property that is less than 100 feet or 100% of the tower’s height.

In any event, the obligation, if any, imposed by a local government on a person or corporation, to purchase insurance, provide proof of insurance or add an individual or entity as an additional insured may be found in a municipal code provision but is rarely included in a zoning ordinance. It appears that only one Chapter of the Fountain Hills Zoning Code mentions an insurance requirement. That provision, 19.06, of the Architectural Review Guidelines, obligates a property owner to purchase insurance under very limited and specific circumstances.

As to the expressed belief that residents would be “uninsured” for any loss or damage resulting from an accident or injury involving a cell tower, Troller and Gildersleeve, as well as Councilmember Friedel, appear not to understand how insurance works. Most, if not all, residents have health insurance, that would cover physical injury resulting from an cell tower related accident and homeowner’s insurance, that would cover property damage.

The providers of this “first party” insurance would pay for the resulting injury or damage, subject to applicable deductibles. Those providers would then have the right to seek reimbursement of the amount they paid from any party found to be legally responsible for the injury or damage. If the legally responsible party is covered by liability insurance the insurance company would pay.

Both Troller and Gildersleeve also appeared to be confused about their right to recover damages from members of the Town Council for their imagined “uninsured” loss. Both contended that members of the Town Council, who voted in favor of the amended ordinance, would be personally liable for any injury or damage caused by a cell tower. Addressing Councilmember, Sharron Grzbowski, attending her last meeting as a town council member, Troller scoffed: “I hope you are moving like out of the country so it’s not going to absolve you because a yes is a yes.”

Apparently, Troller and Gildersleeve are not aware that they cannot recover damages from individual councilmembers for for voting in favor of the amended ordinance. The councilmembers are absolutely immune from personal liability resulting from their legislative actions . See, Bogan et al v. Scott-Harris, 523 U.S. 44 (1998).

During the public comments, John Donnelly, who identified himself as a personal injury lawyer, also raised the specter of litigation. Donnelly envisioned not one, but two class action lawsuits. The first class action, would be brought against the Town by those claiming to have been injured by radiation exposure. A second-class action would be brought by the “very rich people” who live in his neighborhood if the Town allowed cell towers to be built in the wash adjacent to their homes.

Of course, as the Town Attorney observed later in the proceedings, anyone can sue for anything, as evidenced by the two meritless lawsuits brought against the Town by ROT and Skillicorn. The issue is whether they would prevail. It is extremely unlikely that the Town would be found legally responsible, for injury or damage related to cell towers, due to its limited ability to regulate their placement, and inability to regulate based on health concerns, if the facilities comply with federal standards.

The concern that the ordinance did not require the applicant to indemnify the Town

Those concerned about being “uninsured” were also concerned that the amended ordinance did not include a provision that would require the applicant to “indemnify” the Town. Friedel officiously stated that he would not vote in favor of the amended ordinance because it did not include an express indemnity requirement.

Indemnity, like insurance, is not an issue that is ordinarily addressed or that needs to be addressed in a zoning ordinance. The fact, that the ordinance does not address indemnification does not leave the Town “uninsured” as some of the speakers and Councilmember Friedel suggested. The Town has liability coverage. In addition, the fact that the ordinance does not address indemnity does not preclude the Town from addressing the issue in the administrative or approval process.

Concerns over the “lack of transparency”

Matthew Corrigan, a candidate for Town Council, took the opportunity to stir the pot when he criticized the Town Council for a purported lack of transparency. Corrigan claimed that the information provided by Mr. Wesley at the beginning of the hearing was “all new” and had not been made available for review by the Planning and Zoning Commission or the public. That statement was not true. Virtually all of the information in the presentation was included in the online packet for the July 8th meeting of the P&Z, where it was extensively discussed. In addition, all of the information presented was included in the online packet for the Town Council meeting five days before the hearing.

Complaints about a lack of transparency were also based on the Town Council’s determination that it would not to waive the attorney-client privilege by producing the “Campanelli documents”.

Before and during the hearing, concerns were raised that the amendments to Chapter 17 should not be considered until the P&Z and members of the public had been provided with the opportunity to review a document or documents that had been prepared by Andrew Campanelli, one of the attorney consultants the Town retained to assist them in their review. On one of his many websites, AntiCellTowersLawyers.Com, Campanelli describes his practice as representing: “property owners, civic associations and local governments who seek to invoke their civil rights to oppose respective applications for the installation of cell towers and antennas.”

In her public comment, Crystal Cavanaugh asserted that it was “not acceptable” to allow the Town Attorney to withhold information from a reputable expert that was “hired supposedly by the attorney”. During his public comment, Larry Meyers argued that because Campanelli was paid with “our money” his communications to the Town Council should be made available to the public.

At the outset, it should be noted that Ms. Cavanaugh was wrong to suggest that the Town Attorney hired Mr. Campanelli or withheld the Campenelli documents. The Town of Fountain Hills retained Mr. Campanellli and only the Town of Fountain Hills could waive the attorney-client privilege. Here, a majority of the Town Council agreed that the privilege should not be waived.

We can only speculate as to why the Town Council chose not to waive the attorney-client privilege. They may have been concerned that waiving the privilege would set a precedent. They may have been concerned that the document could be used against the Town in an Enforcement Action brought by the FCC. Without regard to the reasons, the Town Council, in the exercise of its discretion, decided not to waive the privilege and the discussion should end there.

Concerns over the bifurcation of the review and amendment of Zoning Ordinance Chapter 17 and Chapter 16-2 of the Municipal Code

Based on input from staff and concerns over resources, the Town Council elected to bifurcate the review of Zoning Ordinance Chapter 17 and Chapter 16-2 of the Municipal Code, where the regulation of SWF’s in the ROW are addressed.

A number of residents, as well as Councilmembers Toth and Friedel, argued that the approval of the amendments to Chapter 17 should be postponed pending the review of Chapter 16-2. A countervailing argument was made that the amendments to Chapter 17 , should be approved now because they provided additional guidance to applicants and included enhancement and safeguards that would benefit residents. In the end it was determined, by the majority, that the balance weighed in favor of approving the amendments to Chapter 17.

Public Comment ends with a threat

April McCormick, who believes that her health has been adversely affected by EMF exposure, was the last speaker during the Public Comment section of the hearing.

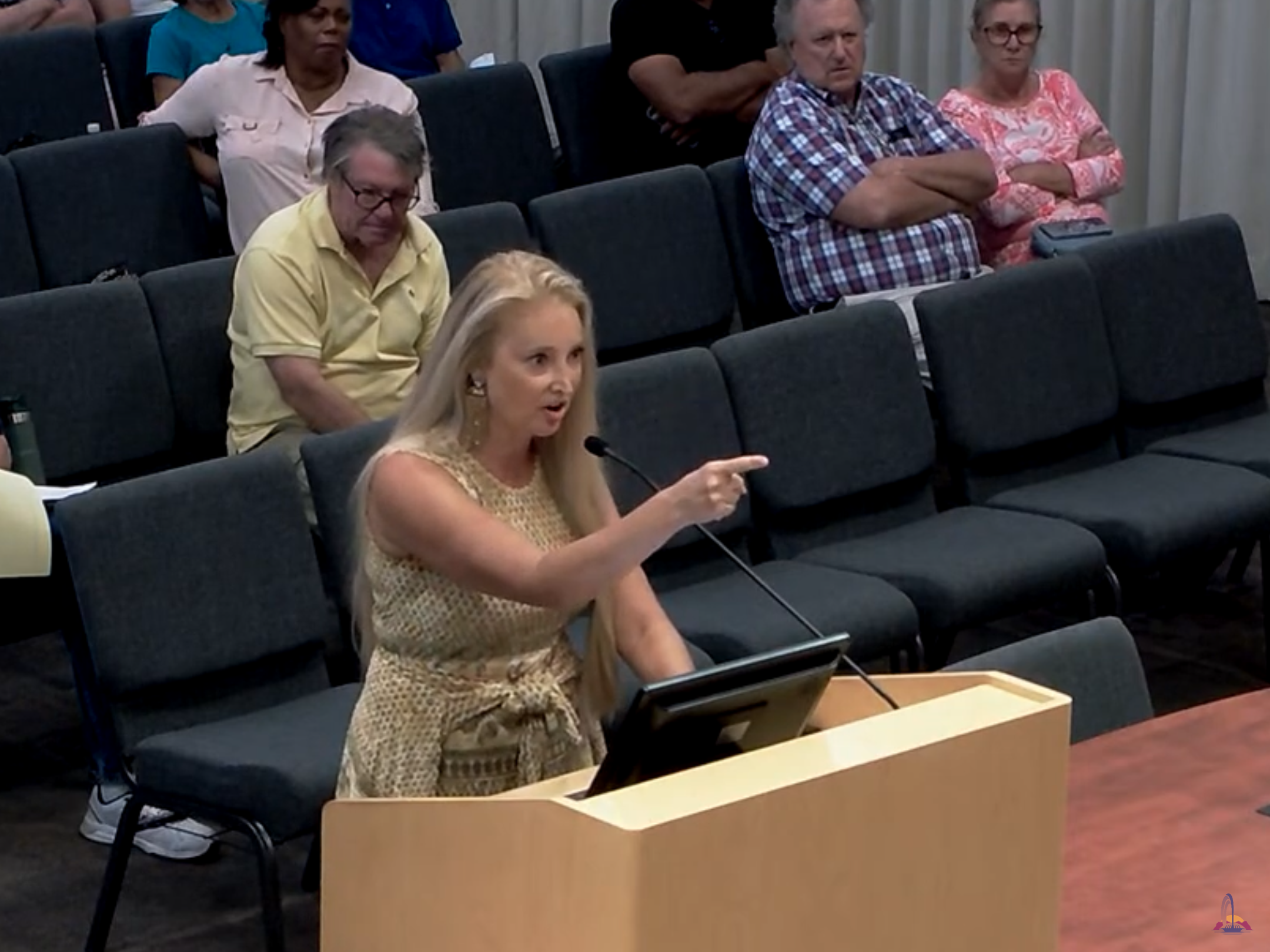

McCormick complained bitterly about the way she and, Andrew Campanelli had been treated and made angry and unfounded accusations against Mr. Arnson. Toward the end of her comments, McCormick bent over the podium, glared up at Mayor Dickey and Councilmember McMahon and proclaimed: “Elections matter! And I’m telling you right now, the only way this is ever going to happen is to get rid of her!” (jabbing her finger at Mayor Dickey) “and her! (jabbing her finger at Councilmember McMahon).

After the hearing was closed Mayor Dickey patiently attempted to address the expressed concerns about the process. Both Mayor Dickey and the Vice Mayor attempted to again explain the limitations on the Town’s ability to regulate the technology based on the limitations imposed by federal law. But, by then, some of the most disgruntled residents had left the building and those that remained were not in the mood to listen.

AFTERMATH

A month later, the bitterness and distrust on display during the rancorous hearing continues to hover over the Town like a toxic cloud. The acrimony is not surprising given the misinformation and disinformation concerning “5G” that has been circulating in the ROT dominated information silos for the past three years. Acrimony, that the three ROT supported candidates, Friedel, Corrigan and Watts have exploited.

What was clearly not appreciated by many of the agitated attendees, but which should have been appreciated by Friedel, Watts and Corrigan, is that when it comes to cell tower regulation, the Fountain Hills Town Council is caught between a rock and a very hard place.

The Town Council can continue to take abuse from a vocal minority of residents who want them to ban or strictly regulate cell towers or it can attempt to appease the minority and invite an Enforcement Action that would be both disruptive and expensive.

It is understandable that members of the public might not appreciate the Town Council’s dilemma. It is not, however, understandable that sitting members of the Town Council and candidates for mayor and the Town Council, do not. Rather, it appears that they are intent on fanning the flames and, if elected, would welcome a fight with the FCC. Serving as an additional, but compelling reason why they should not be elected.